Truly a work of art, this is a glass of cold water in an endless scorching desert.

―Niles Black, Play store review

This is the best RPG story I had ever experienced

―CrickySoupDoupLP, YouTube gameplay walkthrough

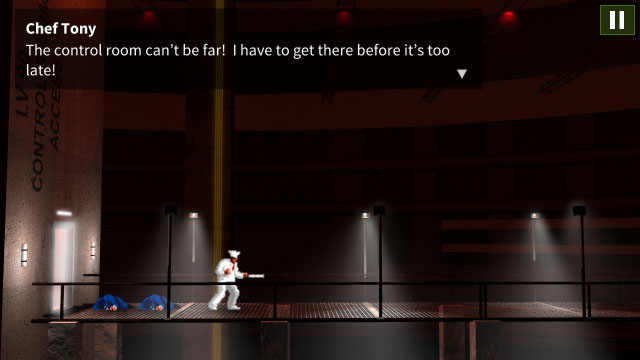

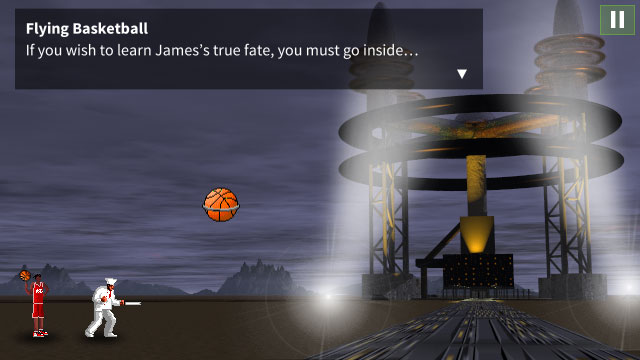

Welcome to the world of JGA: Crossroads of Destiny. In this story-driven RPG, you play as an exiled infomercial chef who must embrace his destiny and restore balance to the world. For this project, I composed an original soundtrack, drew in-game artwork, wrote a 45-page script, and coded the entire game using Unity.

Why does this exist?

At one point, long ago, I made my younger brother a game as a Christmas present, starring him as the protagonist. Only taking about 10-15 minutes to play through, it featured a bizarre storyline involving flying basketballs, a J-shaped fortress, and lots of plot holes. For years, I had planned a sequel to the game–one which would finally explain everything.

However, years of planning merely resulted in numerous false starts and a huge amount of abstract ideas: I had concepts based on RPGs, platformers, sports games, and beat-em-ups. I had even, at one point, created graphical assets for a 3D version of the game that never made it past the prototype phase. It was clear that in order to start development, I needed to focus and actually design something that could reasonably be implemented. I wrote an outline, stripping the game down the most basic elements: the characters, their motivations, and the overarching framework of the story.

Implementation

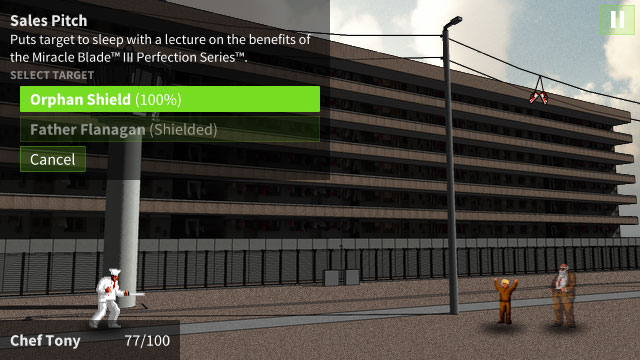

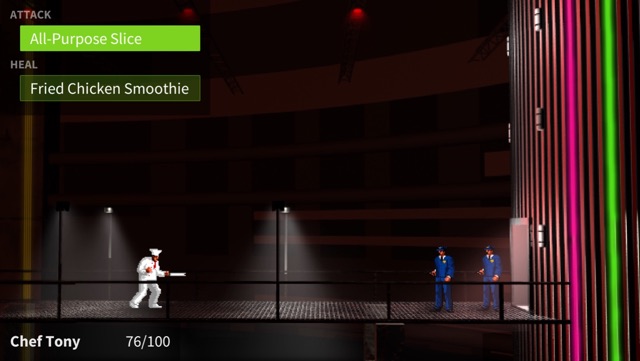

I’ll spare you most of the details of writing the code (the battle system alone features enough class hierarchy and polymorphism to make your intro to Computer Science professor shed tears of joy), but ultimately I settled on the Unity game engine, because it was free, flexible, relatively easy to learn, and also offered the ability to easily build for multiple platforms.

Playtesting

As the game reached a point where it was playable, I began letting various people try it out while I examined their performance to determine what worked and what didn’t. Some of the results surprised me! A few highlights follow.

Why can’t I jump?

To simply development, I had decided to implement the game as a 2D side-scrolling game. However, as an RPG, it was not a platformer, and therefore the only required character movement was left and right. However, a key piece of feedback I received from early informal playtests: “where’s the jump button??”. After this happened several times with several different people, I realized that, despite the lack of a technical need for a jump function, people expected this type of game to have a jump function. After adding one, this problem vanished.

Keyboard or mouse? Yes.

As development on the game progressed, I wanted to make sure it would work and make sense to people. I initially built the battle system to rely on gamepad-based controls, as I assumed that this would make sense since the rest of the game is played that way. However, in early playtests, I found that people kept trying to go for the mouse. I then designed the battle system to be playable with just the mouse and found that then people kept trying to use the keyboard. Finally I realized that I couldn’t get away with half-measures and implemented both mouse and gamepad support.

Stop dumping me in the main menu!

Because the game wasn’t that long and was completely deterministic, there wasn’t really a lot of reason to build a fully-fledged save/load system. Instead, I chose to use a chapter-selection based mechanic, where the game would allow you to reload any previously accessed chapter. However, where this fell apart when when people died in the game. My testers complained that after dying they were forced back to the main menu, where they’d then have to select a chapter. As such, I added a “try again” button to the game over screen, which seemed to address the problem.

Adapting for Mobile

As much as I like PC gaming, I decided that releasing a mobile port would be a good way to reach a wider potential audience. Unity makes it quite easy to build for Android (I ruled out iOS due to the exorbitant costs of a developer license), but since as-is the game required physical inputs, I set about adapting the game to touchscreens. Luckily, thanks to the mouse support, the battle system UI was already reasonably well-suited to touch. However, movement would need to be adapted.

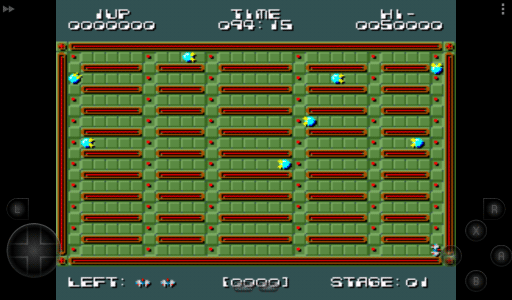

I decided that I’d just look at what other similar mobile games were doing because I didn’t want to reinvent the wheel so to speak. 2D side-scrolling games are not particularly common on mobile, perhaps due to the lack of a physical control method. After trying several different games, it seemed that the most common approach was to use a “touch gamepad”—a semitransparent touch gamepad overlay, where up/down/left/right and buttons were overlaid on the screen:

However, there was a particular 2D side-scroller that caught my eye: I settled on the interaction model of a game called Type: Rider, a typographically themed 2D platformer. Instead of a touch gamepad overlay, it simply made pressing anywhere on the left side of the screen go left, and pressing anywhere on the right side of the screen go right. To jump, you could tap on the side of the screen that you weren’t currently holding.

The primary downside to this control scheme is that it lacks discoverability. Type: Rider uses a tutorial level to familiarize players with the control scheme. However, due to the ridiculously linear nature of this game, control necessities essentially boil down to moving the character right. To determine if this was worthy of concern, I performed some additional tests, with several different players. However, I found that, in general, people would, seeing nothing to touch at all, would touch somewhere on the screen, causing the character to move. Once that had occured, no one seemed to have any issues controlling the game.

Conclusion

Ultimately, I was able to finish and release the game, after nearly a decade of being stuck in my own personal development hell. The key lesson I learned was ultimately one of project management: always focus on the end goal of a project. For every asset you create, ask: how will this fit into the project? Is this really necessary?

The game, while not a smash hit by any means, at least got several highly-positive Play Store reviews! I particularly enjoyed a playthrough posted to YouTube! While it wasn’t a success like TimeStyle, it remains my favorite project I’ve ever created.